This essay entitled “My Buddy’s Hat” also appears in the winter issue, 2013, of the on-line Journal PersimmonTree.org

“There is no glory in battle worth the blood it costs.”

Dwight David Eisenhower

It’s late April, 2011, and already broiling hot at the entrance to the National Infantry Museum and Soldier Center in Columbus, Georgia. This is the recreational outing during my fourth reunion with the guys of Alpha Company. Once again, we’re part of a motley crew of former GIs who served in the 22nd US Army Infantry Division in various wars, a few spouses, and me, the only Vietnam War widow in the group. In spite of the fact that we are here among about two hundred veterans of all ages, our section of the bus – those connected in some way to Dave’s Company back in 1969 – behaves like a merry band of war buddies, joking and teasing, ribbing each other about things that happened long ago in the region of Tay Ninh. They include me in their repartee – as if I had been there, too.

Our bus driver, Ike, a thin, talkative man, lightens the atmosphere further when he chimes in over the loud speaker in his melodious Georgia drawl throughout the two-hour bus ride from Atlanta with quips like: “Whatever you folks do back there behind me, don’t wake me up while I’m drivin’. “

How amazing to be on a road trip with some of the guys who were with my husband forty-two years ago in the jungles of Vietnam.

Each time I’m with these men at a reunion I’m flooded with the feeling that Dave is present among us.

Joe, who carried the code book on the heels of Dave back in ’69, sits next to me. Quiet moments are rare in this group and when they occur I know a memory has been retrieved, wrapped in words like a gift and is about to be presented to me. I’m like a visiting dignitary in these gatherings, beloved and honored, and served morsels of their long ago experience as if they know that I need to be nourished on these trips. This time it’s a mouthful.

“I want you to know that I would have died for him. We all loved Captain Crocker,” said Joe, staring straight ahead at the back of Ike’s driver seat in front of us.

Such strong, spontaneous utterances are normal in this group, but it’s hard to know what to say back except, thank you.

I’m ambivalent about this journey – not about the pleasure of being along with this special group and almost one of the guys – but dubious about visiting infantry tributes and war memorials. My resistance to military fanfare and the seductive power of monuments has helped to sustain me over the years against irrational sentimentality; the state of mind that encourages people to find the good of it all, the notion that going to war in Vietnam was something that had to be. I respect these guys, these survivors who saw their buddies die, but I cannot be convinced that my husband died for a good cause. Can we pay tribute to veterans without joining a “group think” that rationalizes and justifies the violence of war?

I try to do this when I’m participating in military-focused events like this by keeping a look out for inconsistencies, irregularities, the little flaws in the whole cloth of the dramatic, cinematic re-telling of war such as we are about to experience at the Infantry Museum. My vigilance is the evidence of the compromise I always feel at these reunions; I want to be with these people and hear their stories but I don’t want to participate in condoning militarism and military proliferation. I manage these experiences by having little talks with myself along the way; big Ruth is taking little Ruth back to reflect on her early and violent brush with military life.

The museum sits all by itself about a mile outside the heavily guarded gates of Fort Benning and rises up abruptly like the Parthenon in Rome; a monolithic, granite structure in the center of a manicured plateau bordered by Georgia pines. Ike tells us to remember our bus number or risk spending the night on the grass under a tree as we pour out onto the sidewalk like dutiful ants marching to a picnic. This is reminiscent of the instructions we received before we boarded the buses to the Vietnam Wall Memorial in Washington, as if it is the nature of our group to become lost and forgetful children when we travel together. I like this sentiment and I’m glad that someone is watching out for us.

The wide concrete walkway, the huge glass doors, the stone façade in front of us are all grand, solid, modern and sturdy; impervious against tornadoes, hurricanes, and possibly humans. The brochure said it was built by funds from a private foundation and they supposedly cut no corners.

Out back behind the museum are the remnants of the original “temporary” wooden buildings salvaged from Fort Benning. Seven were saved from a recent tear down and sit clustered in two neat rows with a tiny marching area between them; an “authentically recreated World War II Company Street.” These last remaining seven are simple structures thrown up overnight during the troop surge in World War II and never meant to last. Now they’re considered quaint; nostalgic of the old days, the 1940s, when soldiers lived like toughening boy scouts at summer camp and ate from sectional tin plates on long wooden picnic tables in a mess hall resembling a rustic nineteenth century polka dance palace. Even I felt a twinge of historic satisfaction when I saw the old buildings – as if I was viewing an enclave of endangered shacks at Plymouth Plantation or visiting the Alamo – recalling these simple, square, mustard-yellow constructions that were still in use when I lived as an Army wife at Fort Benning for one month in 1966, while Dave completed Ranger and Airborne training.

They’re a lot smaller than I remember. They look like playhouses.

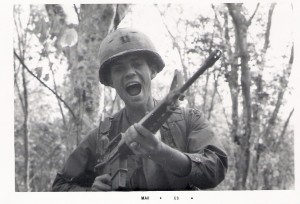

Just before the grand entrance to the museum, our greeter stands ten feet above us on a granite pedestal. He is a bronze statue of a single infantryman, a giant fifteen-foot Gulliver, lunging forward in vintage WWII fatigues and helmet, glistening under the southern sun with a bayonet rifle in the ready position. We gather beneath him and snap photos of each other.

Walking into the vestibule behind him, we are dwarfed again by the domed ceiling three stories above and the broad expanse of cavernous, empty space surrounding us. This is our launch pad, the spot where we must breathe and suck in extra oxygen and take note of the shiny gift shop, the Soldier Store, tucked in the corner on the far left, and inhale the aroma of roast beef from the restaurant on the mezzanine to our right, because – we are about to go to war. Supplies and sustenance might be needed soon. Exuberance is building in the group. My graying companions are possibly recollecting their experiences as young infantrymen forty-plus years ago as we crane our necks to absorb this magnification of space.

“There’s supposed to be a room in here that simulates being in Vietnam,” Ken says, his eyes darting around the space. He was a Captain, an intelligence officer, back in 1969. The others nod in affirmation with serious expressions, glancing at me, at one another, and then up to the soaring ceiling. Did the architect intend to make us feel so small in this place?

No one expresses nostalgia for the old days. Bill aka “Lumpy” is emphatic that visiting the country of Vietnam is not on his bucket list, but the chance to visit a simulation of war as a tourist with old comrades has an appeal. Since the late 1990s the long tide of trying to forget has turned. They are working to recall situations and find people from their days in Vietnam. I sense temperatures rising and hear voices lifting among them. Could they be as nervous and ambivalent as I am about visiting this place?

This is only a museum, I remind myself, but anticipation is building almost as if we are going to war. The folks checking our tickets and stamping our hands for re-entry tell us that we are about to be part of the last one hundred yards, the phrase that symbolizes the job location and duties of the infantry. And don’t miss the I-Max movie about battle, they shout after us. Up ahead, over the heads of the crowd, a darkened tunnel beckons. We make our suggested donation (this is a non-profit organization) and become a troupe of Pinocchios, drawn towards that darkness in front of us, the entrance to the “Last One Hundred Yards Ramp.”

We enter into a filmy half-light after the swinging doors slam shut behind us and glimpse a cartoonish battle-worn landscape lit by candles and campfires. We move along en mass as if we are packed together, row after row, in an amusement park tour boat. I’m reminded of the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disney World where pirates and their victims droop from the windows and balconies of elaborate stage sets except that we are walking through the front lines of a Revolutionary War battle.

Simulated flares careen overhead; life-like soldiers on both sides of us are shooting, being shot at, shouting out to each other, and eventually descending from above with parachutes as we make our way to the World Wars. We creep forward up a small incline as one battle flows into the next and the background sounds change to match the ping, pop and boom of the weapon du jour, from flintlocks to mortars and submachine guns. Each war has its own musical score from Yankee Doodle to Toby Keith. Wherever US infantrymen have fought since the American Revolution, we are among them, watching them portrayed by manikins with strong but haggard faces, slim, muscular bodies, and tattered uniforms.

The movie recommended by our ticket taker features newsreel clips of men in actual battle, shoulder to shoulder, preparing to jump from airplanes, slogging through mud, landing on the beaches of Normandy. Face after face of young men flash by with determined looks and unfathomable thoughts. The camera lingers so close that their young, acned faces become a topographic map of Everyman – so close that I thought I could see their hair grow; these young men barely out of high school still maturing, carrying bayonets and tossing grenades. There is little text or few words amidst the cacophony of moving, jumping, shooting and explosions. The seminal message was that the greatest gift you can give your buddy is protection and courage. You’re not alone; we’re all here to take care of each other. We’re here to die for each other.

Ironically, I’m watching clips of Vietnam with the remnants of Dave’s Company. We passively observe the chaos, the unpredictability, the adrenaline, the testosterone and the waste of war from cushioned seats in air-conditioned comfort.

“What did you think of the movie?” I ask them as we file out. Those who answer are unanimous. “It was great,” they said. “That’s how it is in war. You rely on each other. You need each other.”

I’m sure they’re right. How could one go to war without accepting the standard: “All for one and one for all!” It was when they returned that they had to face being alone with their dreams and memories, but that aspect of war is not so easy to represent and codify. Perhaps that’s why we’re here in this place, this museum, trying to get a handle on what was and what happened.

Four of us enter the Vietnam jungle simulation room. It’s too dark and real for some of the guys. They back away from bamboo encroaching on all sides from floor to ceiling, the Punji stake pit exhibit, and sounds of explosions and drenching rain. Lumpy says, “Let’s get out of here.” We slip out a side door back into the Cold War.

Sandwiched between areas entitled “Securing our Freedom” and “The Sole Superpower,” and graphic representations of the Revolutionary war, the World Wars, the Korean War, Vietnam, and finally, getting right up to date, the Global War on Terror, there is a small circular enclosure called the “family gallery.” Photographs and drawings cover the walls inside and depict decades of soldiers departing from or returning to parents, sweethearts, spouses, and children at home. Scores of pictures show women (presumably wives or girlfriends) waving heroically at train stations, clutching letters to their breast, or sitting surrounded by children arranged next to a portrait of a soldier. Young couples jump into each others arms on tarmacs next to airplanes and cars. In the center, enclosed by these scenes of parting and reunion, a folded flag sits on a pedestal under a glass case. A shaft of light from above shines down on the triangle of red, white and blue. The dedication plaque reads, “to those who don’t return from the last one hundred yards.”

Dick arrives at the display and stands next to me, “I was hoping you wouldn’t see this part,” he says.

I wanted to say that it is the only part of all this that I can really understand. How could I miss this? I have one of these triangles at home.

The folded flag is a powerful image, wrapped tight, full of mute compressed energy. It could be a tri-cornered mandala for some; a symbol in a dream representing the search for completeness, self-unity. Not for me. I find the silence of this flag at the center of this exhibit baffling and scary; a “danger” sign on a back road lit up car headlights. It’s the surrounding photographs that touch my grief spot and stir my sorrow. I would have liked to have been one of those young women in the happy reunion photos, jumping into my husband’s arms after his return. This gaudy triangle in front of me, the representation of sacrifice, the consolation prize, reminds me of something in hibernation.

Even for me – a recipient of the flag– there is an ambiguity about the meaning of this gift. What do the folders and presenters intend to convey when it is handed to the bereaved? Is it a souvenir, a transitional object? What transaction have I entered into by accepting it?

I remember standing under a tree in the cemetery and watching six, crisp and spit-shined soldiers in dress uniforms folding the flag with mechanical precision. I was close enough to catch a whiff of Old Spice aftershave as the flag was about to be presented to me. One could imagine that there is a script that accompanies this oft repeated act of an honor guard folding, pressing, compressing the cloth exactly thirteen times into a period to punctuate the end of a life.

In fact, no “official” text exists that explains the folding and the folds. There is, however, a “generally known script” underlying the folding process (supposedly known by those who do the folding). But, the U.S. Flag Code (Public Law 94-344) states that there is a prohibition against the acknowledgement of the words and they cannot be mentioned in official ceremonies. To do so would be a violation of the First Amendment which requires that verbal expression not create the reasonable impression that the government is sponsoring, endorsing, or inhibiting religion generally, or favoring or disfavoring a particular religion.

The following is the unofficial script represented in all flag folding ceremonies and can be found in many governmental and military manuals even with the above prohibition of public disclosure. The origin of the script is unknown. Some speculate that it may have been written by an unknown chaplain considering the Judeo-Christian overtones. It seems that decoding this experience may not be appreciated by some non-Christians who also consider themselves patriots and who may have received a folded flag on behalf of a deceased veteran. Here is the script from the U.S. Flag Code:

1. The first fold of our flag is a symbol of life.

2. The second fold is a symbol of our belief in the eternal life.

3. The third fold is made in honor and remembrance of the veteran departing our ranks who gave a portion of life for the defense of our country to attain a peace throughout the world.

4. The fourth fold represents our weaker nature, for as American citizens trusting in God, it is to Him we turn in times of peace as well as in times of war for His divine guidance.

5. The fifth fold is a tribute to our country, for in the words of Stephen Decatur, “Our country, in dealing with other countries, may she always be right; but it is still our country, right or wrong.”

6. The sixth fold is for where our hearts lie. It is with our heart that we pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

7. The seventh fold is a tribute to our Armed Forces, for it is through the Armed Forces that we protect our country and our flag against all her enemies, whether they be found within or without the boundaries of our republic.

8. The eighth fold is a tribute to the one who entered in to the valley of the shadow of death, that we might see the light of day, and to honor mother, for whom it flies on Mother’s Day.

9. The ninth fold is a tribute to womanhood; for it has been through their faith, love, loyalty and devotion that the character of the men and women who have made this country great have been molded.

10. The tenth fold is a tribute to father, for he, too, has given his sons and daughters for the defense of our country since they were first born.

11. The eleventh fold, in the eyes of a Hebrew citizen, represents the lower portion of the seal of King David and King Solomon, and glorifies, in their eyes, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

12. The twelfth fold, in the eyes of a Christian citizen, represents an emblem of eternity and glorifies, in their eyes, God the Father, the Son, and Holy Ghost.

When the flag is completely folded, the stars are uppermost, reminding us of our national motto, “In God we Trust.”

After the flag is completely folded and tucked in, it takes on the appearance of a cocked hat, ever reminding us of the soldiers who served under General George Washington and the sailors and marines who served under Captain John Paul Jones who were followed by their comrades and shipmates in the Armed Forces of the United States, preserving for us the rights, privileges, and freedoms we enjoy today.

How whimsical to imagine this symbol of the end as a hat.

My “cocked hat” is still in my possession. I’ve never taken it out of the original triangular plastic case in which it was presented. It sits on a shelf in a cupboard. I didn’t keep it because of what it says in Section 8j of the U.S. Flag Code: “The flag represents a living country and is itself considered a living thing.” (This is why old, tattered flags are ceremoniously cremated.) I kept it because it’s the only object I have that was close to Dave’s body on his trip back from Vietnam in 1969. Perhaps a spell was cast on me during the presentation ceremony. It remains a powerful symbol of his egregious end. A convoluted sentiment, perhaps, certainly not related to patriotism – I can’t recognize myself among the explanation of those folds – but my reasoning is no more inexplicable than the way we have canonized and glorified the act of war and military proliferation in our culture. Disentangling the web of ritual, tragedy, patriotism, war and sentimentality is not for sissies. I can say with honesty that the motivation to keep my flag, untouched, in a safe quiet place for more than forty years is ambiguous. Even Dave might have said, “Don’t keep that. Get rid of it. It’s useless.”

At the Infantry Museum, this small, intimate enclosure with its cocked hat behind glass in the center of the building is the only place that speaks directly to the cost of war. There are no pictures of caskets, or “cases,” as they are referred to these days. As yet, there is no area in the building which acknowledges the wounded and permanently maimed, those who return without limbs or without themselves otherwise intact. Where are the tributes to those survivors with bionic arms and legs who run marathons? Where is the note that acknowledges the fact that since the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, there is an average of one suicide per day among military personnel?

After experiencing the camaraderie of battle in this museum, it seems odd that he’s alone up there, that big bronze guy in the front, the statue of an infantryman who greeted us. So much of the tone and theme throughout the exhibits repeat the notion of brotherhood and willingness to give one’s life for a comrade in arms. Over and over the suggestion that you fight a war “with your brothers” underlies every scene. One leaves with the impression that war begets a “perfect union” rather than horror and chaos. The message is that war is necessary and you perform it as part of a brotherhood. Survival is dependent on teamwork.

I can’t argue with the brotherhood part. I’ve experienced the magical phenomenon of meeting my “brothers” over and over at these reunions. They are as protective towards me as they are towards each others. I feel bathed in unconditional positive regard when I meet them now in different parts of the country and they are a significant part of my healing from grief and my desire to think deeper about my relationship with war and militarism. I would never have visited this museum without them and would have missed an opportunity to re-visit my former life.

But I’m puzzled as I step out the door looking for Ike and bus 225 so we can head back to Atlanta for an evening of dinner and stories. After all the money that was spent on this museum, I wonder why they didn’t spend a little more and put two bronze infantrymen out front, side by side. The war in Iraq alone cost more than three trillion dollars. He looks so lonely up there on his pedestal, as if he’s going the last one hundred yards all by himself. This might sound like a half-cocked idea, but perhaps there’s a message embedded in this lonesome figure. Otherwise, why wouldn’t the creators of this memorial have spent a few more bucks to splurge on another statue and given him a buddy?

Perhaps he is the harbinger of the changing conditions of war. In Michael Stephenson’s historical account of death in combat in ground warfare, The Last Full Measure: How Soldiers Die in battle, he states that soldiers die in the style of their times. World War II was the last war in which opponents met each other face to face on the battlefield. Today’s wars are conducted by remote control. Protection on the battlefield is now a question of body armor and impervious vehicles, not necessarily by who is at your side. Attack comes from malicious devices, land mines, rocket launchers, booby traps and suicide bombers. A trusted comrade cannot die for you anymore as they could have in previous wars, they can only help to carry your body home and keep your memory.

As we board our bus and I take one last glance at our bronze greeter, I’m reminded of Stephenson’s words:

“War is about many things, but at its core it is about killing or getting killed. It is not chess, or a computer game, or a movie, or a book about death [or a museum]. It is, implacably and nonnegotiably, the thing itself.”