Fact or Fiction: It Might Depend on How You Feel

“You’ve got this all wrong. It was cold,” My brother Bob insisted. “The fiercest cold I’ve ever felt.” He pulled his arms in close to his sides and visibly shuddered even though we were standing in a hot, New England kitchen in July, 2014.

He had just read a section of my memoir about my husband’s death in Vietnam in 1969. Bob is two years older than me so I couldn’t attribute his faulty memory to our relative youth back then. I was twenty-two and Bob, twenty-four, when my husband was killed. We were adults. So, why, almost fifty years later, did he recall a broiling hot day in spring as frigid?

I tried a rational approach: “The funeral was on May 29th. It was almost 100 degrees that day. Don’t you remember – Uncle Ephraim had a heat stroke in the middle of it?”

My brother and I are emotionally close in spite of the fact that he is 180 degrees different from me in his political views. We can argue with hammer and tongs about taxes and politics but we’ve never disagreed vehemently about the weather. It felt eerie to be debating something I’d written that was so irrelevant to the event itself. But he continued to insist; it was cold, freezing cold, that day.

This dispute with him about air temperature on one of the most terrible days of my life stayed with me after my book was published and went out into the world. I wondered, briefly, what other details readers/critics might challenge and whether I should worry.

I resolved that it didn’t matter if my brother thought it was cold; that this was his emotional […]

Writing About Traumatic Events

How many times have you heard people say in the aftermath of a traumatic event: “I just can’t talk about it right now.” They are mute, as if the right words have not yet been invented to pinpoint their feelings. Some eventually find expressive relief by writing poems, essays, memoirs, keeping a journal or even describing what happened on Facebook. Those who are visually oriented may speak through the creation of a painting or other art project. There are no rules or even guidelines for self-expression at the boundary of trauma but many who have been through the experience say that describing it to another person does help.

Finding the words

Our body tells us when we’re ready to unpack and codify feelings, to put words or other artistic expression around painful experiences. For some, even recollection of the experience can stay tucked away for years and emerge years later, perhaps when another life-changing event dredges up old memories. A Vietnam War veteran once shared with me that he didn’t speak about the war he experienced until years later when his son was about to be deployed to Desert Storm in the early 1990s: “It hit me like a ton of bricks – my son might be about to experience the same horrors that I had witnessed. I had to start talking, sharing my own experience, after twenty years of silence.”

Owning the story

Sometimes the burden of owning the story is so great that there is a need to fictionalize and tell it as if it happened to someone else. It can take months or years to become comfortable with the telling. Whatever the starting point, be kind to […]

Sparking the Writer’s Imagination

Let’s agree on one thing: the writer’s imagination is impossible to describe. But, for some of us, life without writing is also impossible. Is there a secret behind the sparking of imagination? Except for making ourselves sit down and start writing, it’s difficult to say what makes those words jump onto the page. It helps to believe that our writing matters, especially to us. Anne Lamott described in Bird by Bird that writing matters because of the spirit. “Writing and reading decrease our sense of isolation. They deepen and widen and expand our sense of life: they feed our soul. When writers make us shake our heads with the exactness of their prose and their truths, and even make us laugh about ourselves or life, our buoyancy is restored. We are given a shot at dancing with, or at least clapping along with, the absurdity of life, instead of being squashed by it over and over again. It’s like singing on a boat during a terrible storm at sea. You can’t stop the raging storm, but singing can change the hearts and spirits of the people who are together on that ship.”

It’s important to write. Storytelling is important – in words or paintings. Expressing the imagination on the page (or on canvas) restores our soul. But, there is also the mystery of why we stop ourselves from self-expression and how to get the process rolling again and pour yourself into the work. If you are in the area of Mystic, CT on September 25 or October 7, 2017, join me at the Mystic Museum of Art for […]

If you want to write – a book! Part I

“Wanted: someone willing to sit for hours in front of a blank page and come up with words and sentences which will hopefully become riveting fiction, compelling memoir or beautiful poetry. Financial compensation: potentially zero. Benefits: an excuse to avoid working, housecleaning, laundry, and exercise. “

During a recent promotional event for the People of Yellowstone book at the Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park, many visitors asked me if I knew when Old Faithful would erupt, but some stopped by our display table to peruse the book and ask questions about writing. Several said that they would like to write a book, too. Some imagined they would write fiction, but most wanted to write about their own life.

“How do you begin a memoir?” they asked. “What’s the difference between an autobiography and a memoir?”

Why do people think they want to write a book? I asked myself.

I’m not sure if I can answer this for others, but I do know that writing is a wonderful and mysterious heroic journey during which it’s possible to make amazing discoveries about our self and the world.

“Heroes take journeys, confront dragons, and discover the treasure of their true selves,” says Carol Pearson, author of The Hero Within. I think we can say the same thing about initiating a writing project. It’s a heroic feat. But how does it begin?

Most of us wouldn’t consider entering into hand-to-hand combat or a tennis tournament without some training, but to accomplish a piece of writing – a short story, essay, or even a book – it is possible to hone your skills on the job. The first requirement is to put words […]

Truth Be Told

“Do you swear to tell the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?” We’ve heard this intimidating oath on every television show with a courtroom scene. Fortunately, writers of memoir and personal essay don’t have to make this declaration – at least under oath. Or, if they did, it would be with the caveat that, “This is my truth. This is the way it was for me, so help me Goddess of Imagination.”

It turns out that “truth” has many levels of being, depending on what one is writing about. For most of us, our truth is what we think we remember. Other people might recall the same event differently, but if what you are writing is a memoir about your life, then even other witnesses, like your brother or sister, might remember details differently than your recollection. This is an important concept to keep in mind when writing your story because, if you are swayed to consider some other rendition, based on what someone else claims is the almighty truth, you may not get to the essence of what you are after.

Intention matters. As Sondra Perl and Mimi Schwartz describe in Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction, “If our intent is to capture the messy, real world we live in, we fulfill the first obligation of creative nonfiction. Intent helps us resist the urge to change facts, just to make a better story. It stops us from telling deliberate lies, even as we let our imagination fill in details we only vaguely remember.”

In my memoir, Those Who Remain: Remembrance and Reunion After War, describing my experience of […]

Musings on Memoir

In memoir, a self is speaking and rendering the world. The real subject is your consciousness in the light of history. The objective is to be personal and impersonal all at once. In a sense it is to be a witness and a storyteller.

The hallmark of memoir is the expression of both Now and Then. It is a kind of shuttling back and forth between the past and present, interrogating the experience back then and expressing what that experience means to us now.

We can also think about this as the “I” that was then and the “I” that is now. Or, imagine that your present self is having a conversation with your much younger self.

Memoir begins with a kind of intuition of meaning. The event itself usually happened years ago and a memory, a scene, lingers. I remember weeping in a kitchen in a lonely apartment in a foreign country in 1968 and devouring a box of graham crackers – a big box. Whenever the memory came back, I was uncomfortable. When I eventually described the scene by writing about it, the events before and after came flooding back and I started to get closer to the story.

Memories survive on fleeting things – a wisp of a fragrance, a plaid shirt your father wore, a song that reminds you of another song. These details are the starting point for the deeper story..

Writing memoir is a way to figure out who you used to be and who you are today. It is mental and emotional time travel and sometimes it might involve actual travel.

The memoirist Patricia Hampl wanted to understand who she was as a free-thinking […]

What is Memoir?

Beginning a memoir project is like being an explorer of unexcavated territory, except that territory is within you. You are an anthropologist, a psychologist and a sky diver all at once without leaving your writing table. You take risks on the journey as you delve deeper and deeper into the ravines of memory, but the journey itself is your challenge, a way to stretch yourself and grow as a writer.

A memoir is a story that is true. It can consist of looking back at a single summer, or the span of a lifetime. It is some aspect of life, some theme about which you want to reflect so it becomes a process of unearthing memories and then turning them over and over like a stone embedded with fossils. The more we look the more we see.

There are two basic ingredients in a strong memoir. The first is honesty. The memoirist makes a commitment to tell the emotional truth. Sometimes when the writing is not coming easily, it is often because we’re avoiding what needs to be written. It’s not about baring secrets – it’s simply telling the emotional truth about what you’ve chosen to write about.

Russell Baker told the story of writing a complete manuscript – 450 pages – of a well-researched and documented family story. He included a slew of facts about his family’s genealogy and history. But in the end he realized that, although he was accurate in the reporting of facts about his family, he had been dishonest about his portrayal of his mother. He said, “I had been unwilling to write honestly… and that dishonesty left a […]

Write, Eat, Walk, Write: Food for Thought

One of my challenges in the writing process is how to stay connected to whatever I’m working on and enough distance, at the same time, to have a perspective on what I’m trying to say. Sometimes writing can feel like I’m looking through the wrong end of a telescope. I can work for hours laying down sentences and still feel I am not quite “there” on the page. My usual impulse is to get up and go to the refrigerator, just to check and see if something delicious has magically appeared. Even though I’m the one who stocks the frig, something new and different might have arrived mysteriously between paragraphs.

Amazingly, this little trip away from the desk helps the writing process almost instantly. As soon as I stand up from my desk, a sentence will reorganize itself in my head. Jonah Lehrer says in his book Imagine: How Creativity Works that this is the “outsider” problem. A writer reads her sentences again and again and very soon begins to lose the ability to see her prose as a reader. (In other words, I think I know exactly what I’m trying to say. I think I’m being clear, but that’s because I’m the one saying it.) A writer must reread and edit as if she knows nothing and doesn’t know what these words mean. She must somehow become an outsider to her own work. But how can we achieve this?

Novelist Zadie Smith suggests putting a finished manuscript in a drawer – a year is ideal, she says, or as long as you can manage – so that you can become more of a stranger to your book and eventually read it in a new […]

When Friends Ask for a Critique of Their Writing: The Science and the Fiction

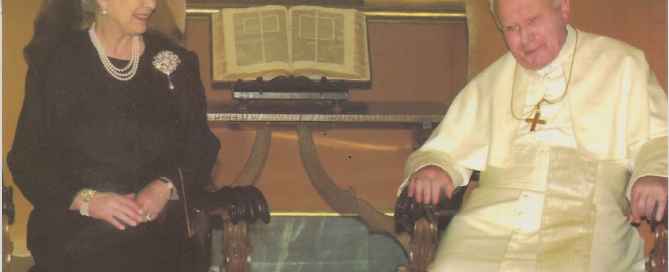

HRH could be conferring with a friend about her book, but perhaps she should have asked Ray Bradbury. Ray was not only a highly motivated and prolific writer, but also a ferocious reviser. He said, “When you write – explode – fly apart – disintegrate! Then give yourself enough time to think, cut, rework, and rewrite.” If and when he did show his work to others before publication, he had already logged double-digit revisions.

But, most of the rest of us earthling writers need support and encouragement along the road to the finished product. There are those writers who show their manuscript to no one until they think it’s ready for publication, but often, when I’m still revising, I like a nudge now and then from a carefully chosen reader who will be honest enough to say that they have no sense of what I’m trying to say, or they lost interest after the first paragraph, or they just couldn’t figure out what my characters were trying to do. This usually happens when I don’t know what I’m trying to say and I’ve wandered off into a thicket of ideas. My reader is not going to tell me what to do or how to find my way, however they might offer a clue or notice that there is too much of something and not enough of something else. Perhaps I won’t agree with my helpful reader – but I was the one who asked! Now I can decide if and how I’ll revise.

Something mysterious happens, though, when a friend asks me to read their work. Suddenly, in spite of having critiqued many manuscripts, I doubt my […]

Truth and Consequences: When family and friends see themselves in your writing

(a workshop presented at a meeting of the SE Connecticut Authors and Publishers Association in Groton, Connecticut, October 21, 2013)

People will always assume that what you write is true – whether it’s fiction or nonfiction.

We cannot know in advance what people will be offended by – and sometimes you will be shocked. They may resent that you haven’t included them enough in your story.

Vivian Gornick – author of “The Situation and the Story” says that good writing must do two things. It must be alive on the page and it must persuade the reader that the writer is on a voyage of discovery.

Writers of all genres wrestle with putting autobiographical material in their work – and writing things in which friends and relatives might recognize themselves.

For writers who write memoir this is an especially important question.

In fiction you can use false names, new settings, or even a different ending to the story. Memoir offers no such hiding places.

With family stories, the stakes are particularly high – especially if family members are still alive. You have to make ethical and practical decisions at every stage of the writing.

You have to decide – what is yours to explore and what should be respectfully left out.

(a large part of this decision is related to what really needs to be in the story. There are some things that should be left out simply because they don’t actually contribute to the story)

Every writer has to make the determination of what is too private and how to know when enough has been said and all writers approach this control differently.

For example, Paul Austin, an emergency room physician who wrote a memoir entitled: “Something for the pain” wrote about his feelings […]