The Secret Annexe in Otto Frank’s factory (top floor of the middle building), Amsterdam.

When Otto Frank read his daughter’s diary for the first time after her death in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, he discovered something new about Anne. “Every parent should realize that it is not possible to entirely know your children,” he described in an interview in 1979.

This is a surprising observation, considering that the Frank family, along with four other people, lived together 24-hours per day, for more than two years when they hid from the Nazis during World War II. Not only were they each other’s only companions, they lived in a tiny attic space about the size of a one-car garage above Otto Frank’s factory. Workers making pectin (a substance used for making jelly) continued to work on the floors beneath them requiring the fugitives above to be completely silent during work hours. Only a select few who worked below knew about the secreted inhabitants.

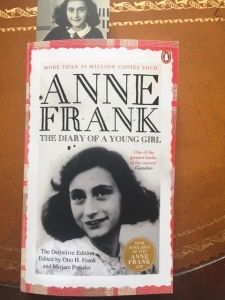

Anne was thirteen when she, her older sister, and her parents went into hiding from the Nazis who occupied Amsterdam, but she already aspired to be a writer. Initially, the red-plaid fabric covered diary she kept while hidden was the continuation of a writing routine. She started recording her thoughts and observations on her thirteenth birthday in June 1942, unaware that within one month she would climb three, steep flights of stairs to a space where she would enter isolation with her family from the rest of Amsterdam for more than two years.

Anne was thirteen when she, her older sister, and her parents went into hiding from the Nazis who occupied Amsterdam, but she already aspired to be a writer. Initially, the red-plaid fabric covered diary she kept while hidden was the continuation of a writing routine. She started recording her thoughts and observations on her thirteenth birthday in June 1942, unaware that within one month she would climb three, steep flights of stairs to a space where she would enter isolation with her family from the rest of Amsterdam for more than two years.

When Anne began her diary she wrote, “Writing in a diary is a really strange experience for someone like me. Not only because I’ve never written anything before, but also because it seems to me that later on neither I nor anyone else will be interested in the musings of a thirteen-year-old girl.” She chose “Kitty” as the recipient of all her musings, a device that freed her from the loneliness of writing. Kitty was an imaginary listener who offered her unconditional regard and acceptance.

For the next two years she wrote detailed descriptions of daily life including overheard conversations, the behavior of her companions, her opinions of herself and others, her moods and desires, and inferences about what might be going on in the world. Listening periodically to a radio was the only connection to world news and one broadcast, a year into their seclusion, encouraged people to keep diaries and letters so that they could be published after the war. This news sparked Anne to go back and revise her diary entries to include everything she could remember.

She also wrote short stories and kept a log of “great sentences by famous writers,” but her notes to “Kitty,” was the place where she stored her ideas that could be shared with no other at the time – and she shared prolifically.

When I visited the cramped rooms at 263 Prinsengracht in Amsterdam where the Frank family and four others lived above the factory during a recent trip to Amsterdam, I was reminded that nothing kept Anne from telling her story. She captured her observations with detailed description, used the five senses, and embraced all the resources she had to create a first-person account of a world that comes alive on the page. She used her relationship with writing to create privacy and self-comfort. She not only aspired to be a writer, she was a writer. She read, she wrote and she revised in spite of all obstacles until August 1945 when the Nazis arrived in the attic.

The next time I’m lost for words or think that I have writer’s block, I’ll ask myself: What would Anne do?