The first time I met the survivors of Alpha Company of the 2/22 Infantry in 2006, I was scared. It had been almost four decades since my husband, Capt. David R. Crocker, Jr., died in Vietnam in a booby-trapped bunker. I had never heard a first person account of precisely what happened, and I still wasn’t sure I was ready to hear the stories. What was I afraid of? Perhaps simply the peeling back of the protective layer of years since I was informed of the tragedy on that warm spring day in May, 1969. Back then, I had avoided the nightly newscasts by Walter Cronkite. I couldn’t bear to see bloodied young men carried out of battle. Before the worst happened, superstition about what might protect my beloved governed every move I made. Charmed thinking was my armor.

The first time I met the survivors of Alpha Company of the 2/22 Infantry in 2006, I was scared. It had been almost four decades since my husband, Capt. David R. Crocker, Jr., died in Vietnam in a booby-trapped bunker. I had never heard a first person account of precisely what happened, and I still wasn’t sure I was ready to hear the stories. What was I afraid of? Perhaps simply the peeling back of the protective layer of years since I was informed of the tragedy on that warm spring day in May, 1969. Back then, I had avoided the nightly newscasts by Walter Cronkite. I couldn’t bear to see bloodied young men carried out of battle. Before the worst happened, superstition about what might protect my beloved governed every move I made. Charmed thinking was my armor.

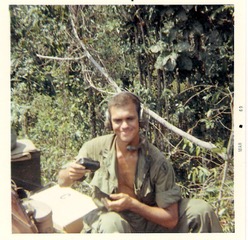

Capt. David R. Crocker, Jr.

War stories are hard for both the teller and the listener. For some people “the beginning “ – that first telling – might not happen for years after the event. Veterans and other survivors of war may hold back their untold stories for decades. Despite their courage on the battlefield, describing that experience requires a reach back down into gut-wrenching details that they had tried hard to forget, back to a place where they may have felt guilty to be a survivor.

But, remembering has its power, too. Meeting the men from Dave’s company and hearing their stories of life with him in Vietnam was my first big step towards a kind of healing, and an understanding of what had actually happened in Vietnam. Listening to them gave me a context and enabled me to write my story. They created my safe harbor for exploring feelings, listening, and telling. Writing helps.

Today, almost fifty years after my personal tragedy in the war, I welcome the eighteen intensive hours of graphic detail in the documentary created by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. These stories need to be told while there are still people living who survived the fire fights, jungles, dust, red ants, foot rot, leeches, and personal humiliation of this war.

As I watch, I’m checking in with my personal experience and remembering the stories of my many reunions with the guys of A Company – once I had the courage to attend.

In the documentary, I welcome hearing about the war from the perspective of the Vietnamese. There is no satisfaction that comes from watching this war unfold – just confirmation. The inexplicable takes shape as the war is fanned from embers into a raging inferno – and for what reason?

I would not have been able to watch these Technicolor atrocities twenty years ago, but, today, I’m prepared for the violence and sadness. Can art help us from repeating another heinous war? This is the only payoff I can imagine for watching eighteen hours of destruction spread over ten evenings on public television.

The Vietnam War cost the lives of more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers, and stole the youth of millions. I find myself looking for Dave, age twenty-five, among all those innocents.

Ruth W. Crocker is the author of Those Who Remain: Remembrance and Reunion After War.