My friend Martha from Oak Ridge, Tennessee has started to write about growing up in a town created by the efforts to build the atomic bomb. Oak Ridge was one of the areas dedicated to the Manhattan Project. Overnight, an entire town was built up in which every adult was somehow connected to the develop of, and the building of, the most lethal weapon the world had ever known. Martha’s father was a brilliant young scientist. Her mother was from the small sleepy town of Sugar Tree, TN. Today, Martha is an accomplished singer and songwriter and she is just beginning to tell her story in prose. She has come to the realization that the best you can do is to tell your story and hope that you can inspire and encourage others because of your journey.

Here is the beginning of Martha’s story about the events that shaped her life and all of our lives from that time forward.

Dogwood Daughter: 3 ANGELS PROJECT

Postcards from the Secret City – In Search of my Atomic Childhood

Recently, a new book titled The Girls of Atomic City, the Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II, by Denise Kiernan, was published. It’s been a best seller, not only here in Oak Ridge, but even landed on the New York Times bestseller list.

Kiernan’s book features interviews with the now very old women who came to the Secret City, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, during WWII to work on the Manhattan Project. Little did they know, at the time, that they were working on an atomic bomb, the bomb that would ultimately be dropped on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945, ushering in the dawn of the Atomic Age.

My mother was one of those girls of the Atomic City. A 20 year old farm girl from Sugar Tree, Tennessee, she arrived in Oak Ridge in 1944. She found work as a ‘climber’ at the K-25 Uranium Enrichment Plant. ‘Climbers’ were slender, strong young women who climbed all over the immense vacuum tubes in what was, at that time, the largest building under one roof in the entire world. Her job was to search for leaks.

She considered the exciting war years as the best years of her life. No doubt, they were exhilarating, especially for the young women of Oak Ridge, thrust into the heady atmosphere of danger, secrecy, and patriotic zeal alongside brilliant and, for the most part, young and single scientists and engineers.

My dad was one of those brilliant young men, having graduated from the Rice Institute (now Rice University in Houston, Texas) at the age of 18. He had arrived in Oak Ridge with one of the early groups who worked on the Manhattan Project in a nondescript looking office building on Manhattan Island in New York City.

In reading The Girls of Atomic City, I’m struck by the justifiable pride in the accounts of women who are now in their 90s. Like my deceased mother, they remember the WWII years as exciting and glorious: I’m sure they were. I’m sorry not to have experienced that part of Oak Ridge history.

I am one of the daughters of that glorious and heroic WWII generation, the mothers and fathers who, for good or bad, harnessed the energy of the sun and unleashed it on the world. And though their nuclear research and development was also applied to many peace time uses, it was bomb production that was and and continues to be the real bread and butter of Oak Ridge, for bomb production did not halt after the close of WWII. On the contrary, it ramped up exponentially during the Cold War and retrofitting and maintaining nuclear warheads is still big business in our little town.

I’m a Cold War baby. I was born in Oak Ridge, Tennessee in 1952. I’m still here.

The experience of the children of the Cold War in Oak Ridge was not anything like the heady days their parents experienced during WWII. The Cold War years were relentlessly threatening, with drills, sirens, bomb shelters in our homes and the ever present knowledge that Oak Ridge was, along with Washington D.C., at the top of the Russian target list.

In the late 80s and early 90s, we learned some other dirty secrets about our childhood hometown: many years of horrific environmental devastation and what seemed to have been routine exposure of the population to heavy metals as well as chemical and radiological toxins that were knowingly inflicted on workers and residents by the ‘Masters of the Universe’ who were the directors of the multi billion dollar business of manufacturing nuclear weapons.

The veterans of the Oak Ridge Manhattan Project have not been reticent in telling their stories about WWII. But for some reason, their children, the children of the Cold War, have been very quiet.

Maybe we’re afraid of being labeled as whiners, since we were cosseted and coddled with federal largess in our exclusive and prosperous little federal enclave. But, it’s been my experience that, when we Cold War babies get together one on one or in small groups, not all of us have glowing memories about everything in our atomic childhoods.

I’ve undertaken my own project: I’m writing a memoir. It’s not a historical document, but rather a personal reflection on my own experience growing up in this ever so strange little town. My memories are not all bad, but they’re not all good either. It’s hard not to look back on those Cold War years in which thousands of nuclear warheads were manufactured and stockpiled, without a sense that there must have been some mass insanity going on.

Right now, my working title is Postcards from the Secret City: My Atomic Childhood.

A couple of weeks ago, I drove over to the east end of town, my old neighborhood, and took some photographs. I’ve been photographing the old neighborhoods and cemeteries as I write.

Will I ever publish my memoir? Maybe. Honestly, I’m not sure yet. But in the meanwhile, I’ll share a few of my recent photos of my old stomping ground on the other side of town.

Be well and good luck. Martha Maria

This is one of the old cemeteries, a family plot, which was left when the federal agents seized the land that became Oak Ridge in 1943. These little cemeteries, which always seemed, to me, the saddest places in the world, dot the entire city, in the most unlikely places. This one is behind an old E-2 cemesto on lower Georgia Ave. There are 92 such family cemeteries in Oak Ridge. As an aside, the old war time houses, which are constructed out of cemesto (pressed asbestos and cement) will stand forever, though they were never intended to last for more than ten years. Why? The asbestos makes them prohibitively expensive to knock down.

Next stop, Atlanta Road. We moved to Atlanta Road when I was three. Before that, we were in a cemesto on Pacific Road. We lived on Atlanta until I was eight.

Looking up Atlanta Road from the sidewalk in front of the house where we lived.

The old house where we lived on Atlanta Road. The carport was not there, nor was the driveway. The front picture windows (where my friend Esther fell out) are the same size but have been replaced with new vinyl ones, replacing the aluminum frames. The house was not bricked when I lived there either. It was sided with maroon red cedar shakes.

The old radio station. Yes, Oak Ridge used to have a radio station. I think the ATO part of their call letters stood for ‘atomic.’ Their studio office and tower were only about two blocks away from our house on Atlanta. I was a big fan of WATO, and listened to it every morning while I sat in the rocking chair. The story hour was broadcast at 8:00 a.m. After story hour, Mother and I listened to the popular music of the day while Anita was at school and Daddy was working at K-25.. I remember wondering how all those bands got in and out of that tiny building so quickly. I had no conception of recorded music: we didn’t have a record player.

This is, I think, the last WWII era dormitory building still standing. Single men and women without families were housed in dormitories during the War, where they shared common baths. No kitchen facilities. Other than this one, which is still a dormitory but now privately owned, the dorms have all been knocked down. My mother and father both lived in dormitories during the war. After they got married, they lived in an E-2 apartment at the corner of New York and Vermont Avenues. That E-2 is gone now too, replaced by one of the medical buildings in the hospital complex.

Dormitory Corridor

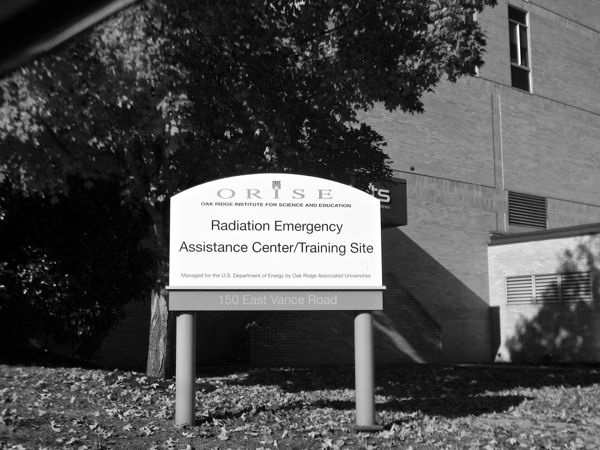

Just in case….of an accidental exposure at one of the nuclear sites. A lot of research has been done here on nuclear medicine, some laudatory, some not. I would recommend reading a book titled The Plutonium Files if you have an interest in such things.

born at OR Hosp in March ’47. we lived in a classic flattop off Illinois Ave along the creek where the synogogue would be. Moved up to 153 California Ave til may 54. I went to Elm Grove Schoo til we moved to Kingston TN in May 1954. I did not complete 1st grade (family joke). Daddy fought in the Pacific and came home to work shifts at k25 for 38 yrs.